Transaction - way to group several writes and reads into a logical unit.

Either the entire transaction succeeds (commit) or fails (abort, rollback).

To simplify programming model for applications to access the database.

ACID

In practice, one database’s implementation of ACID does not equal another’s implementation. For example, there is a lot of ambiguity around the meaning of isolation.

Atomicity

Something that cannot be broken down into smaller parts.

Ability to abort a transaction on error and have all writes from that transaction discarded. Perhaps abortability would have been a better term than atomicity.

If the writes are grouped together into an atomic transaction, and the transaction cannot be completed (committed) due to a fault, then the transaction is aborted and the database must discard or undo any writes it has made so far in the transaction.

No worry about partial failure by giving an all-or-nothing guarantee.

Consistency

You have certain statements about the data (invariants) that must always be true in all sources.

It is a property of the application to define these invariants, if you write bad data that violates these invariants, the db can’t stop you.

Isolation

Concurrently executing transactions are isolated from each other. Each transaction can pretend it’s the only transaction running on the entire db.

Durability

Once a transaction has committed successfully, any data written will not be forgotten, even if there is hardware fault or db crashes.

Usually involves write-ahead-log or similar. Or that the data has been successfully copied to some numebr of nodes if we mean replicated db.

In practice, there is no one technique that can offer absolute guarantees.

Weak Isolation

Ensure some level of isolation but not one-by-one transaction processing.

Read Committed

No dirty reads

When reading to a db, you will only see the data that has been committed.

For a transaction that has not yet been committed or aborted, another transaction should not see the uncommitted data.

How to implement: For every object that is written, the db remembers both the old commited value and the ne wvalue set by the transaction that currently holds the write lock. While a transaction is going, the other transactions are simply given the old value.

No dirty writes

When writing to a db, you will only overwrite data that has been committed.

If a later transaction overwrites an uncommitted value of a previous write part of a transaction that has not been committed - this is a dirty write.

This levels avoids some kinds of concurrency problems too.

How to implement: This is part of many databases, default settings, using row-level locks. Hold the lock until the transaction is committed or aborted.

Snapshot Isolation (Serializable / Repeatable Read)

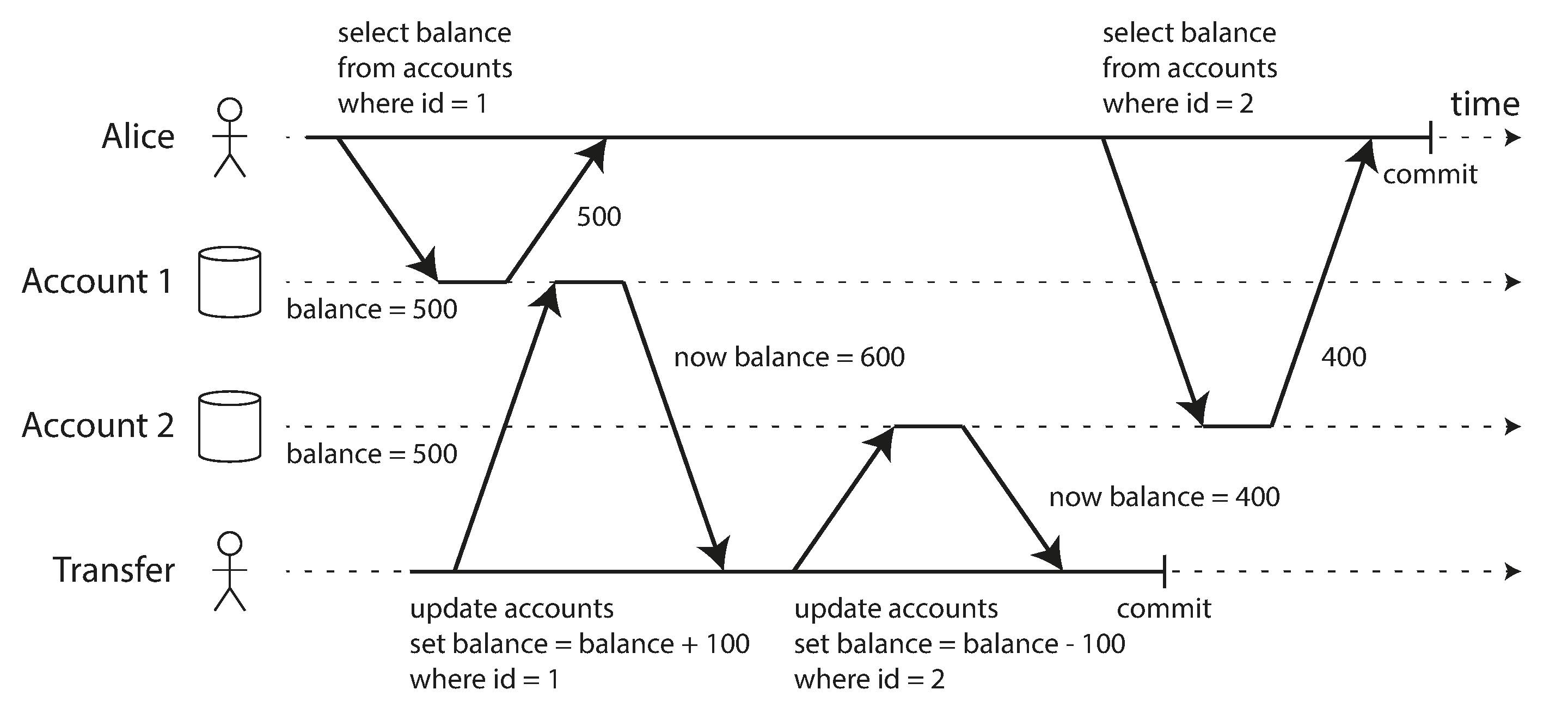

Read Skew/Nonrepeatable Read: With Read commited, you observe the db in an inconsistent state.

Read Skew is considered acceptable under read committed, but not under situations such as backups, analytics queries and integrity checks.

Solution: Snapshot isolation

Each transaction reads from a consistent snapshot of the database (all the data that was committed at the start of the transaction.)

Implementations use write locks to prevent dirty writes, but reads do not require any locks. Readers never block writes and writers never block readers.

The DB must potentially keep several different committed versions of an object (bc in-progress transaction may need to see the state of the db at different points in time). technique called multi-version concurrency control MVCC.

If a database only needed to provide read committed isolation, but not snapshot isolation, it would be sufficient to keep two versions of an object: the committed version and the overwritten-but-not-yet-committed version. However, storage engines that support snapshot isolation typically use MVCC for their read committed isolation level as well. A typical approach is that read committed uses a separate snapshot for each query, while snapshot isolation uses the same snapshot for an entire transaction.

Visibility rules

An object is visible if both of the following conditions are true:

- At the time when the reader’s transaction started, the transaction that created the object had already committed.

- The object is not marked for deletion, or if it is, the transaction that requested deletion had not yet committed at the time when the reader’s transaction started.

The lost update problem

When application reads some value from the db, modifies it, and writes back the modified value. If 2 transactions do this concurrently, one of the modifications can be lost, bc the second write does not include the 1st modificaion.

The later write clobbers the earlier write.write

Atomic write operations

They remove the need to implement read-modify-write cycles in application code.

When atomic operations can be used, these are the best choices.

Implementation: taking an exclusive lock on the object when it is read so that no other transaction can read until the update has been applied.

Explicit Locking

BEGIN TRANSACTION;

SELECT * FROM figures

WHERE name = 'robot' AND game_id = 222

FOR UPDATE;

-- Check whether move is valid, then update the position

-- of the piece that was returned by the previous SELECT.

UPDATE figures SET position = 'c4' WHERE id = 1234;

COMMIT;The FOR UPDATE clause indicates that the database should take a lock on all rows.

This works, but to get it right, you need to carefully think about your application logic. It’s easy to forget to add a necessary lock somewhere in the code, and thus introduce a race condition.

Automatically detecting lost updates

Allow the transactions to execute in parallel, and, if the transaction manager detects a lost update, abort the transaction and force it to retry its read-modify-write cycle.

A plus is that db can implement this in conduction with snapshot isolation.

Replication scenario

A common approach in such replicated databases is to allow concurrent writes to create several conflicting versions of a value (also known as siblings), and to use application code or special data structures to resolve and merge these versions after the fact.

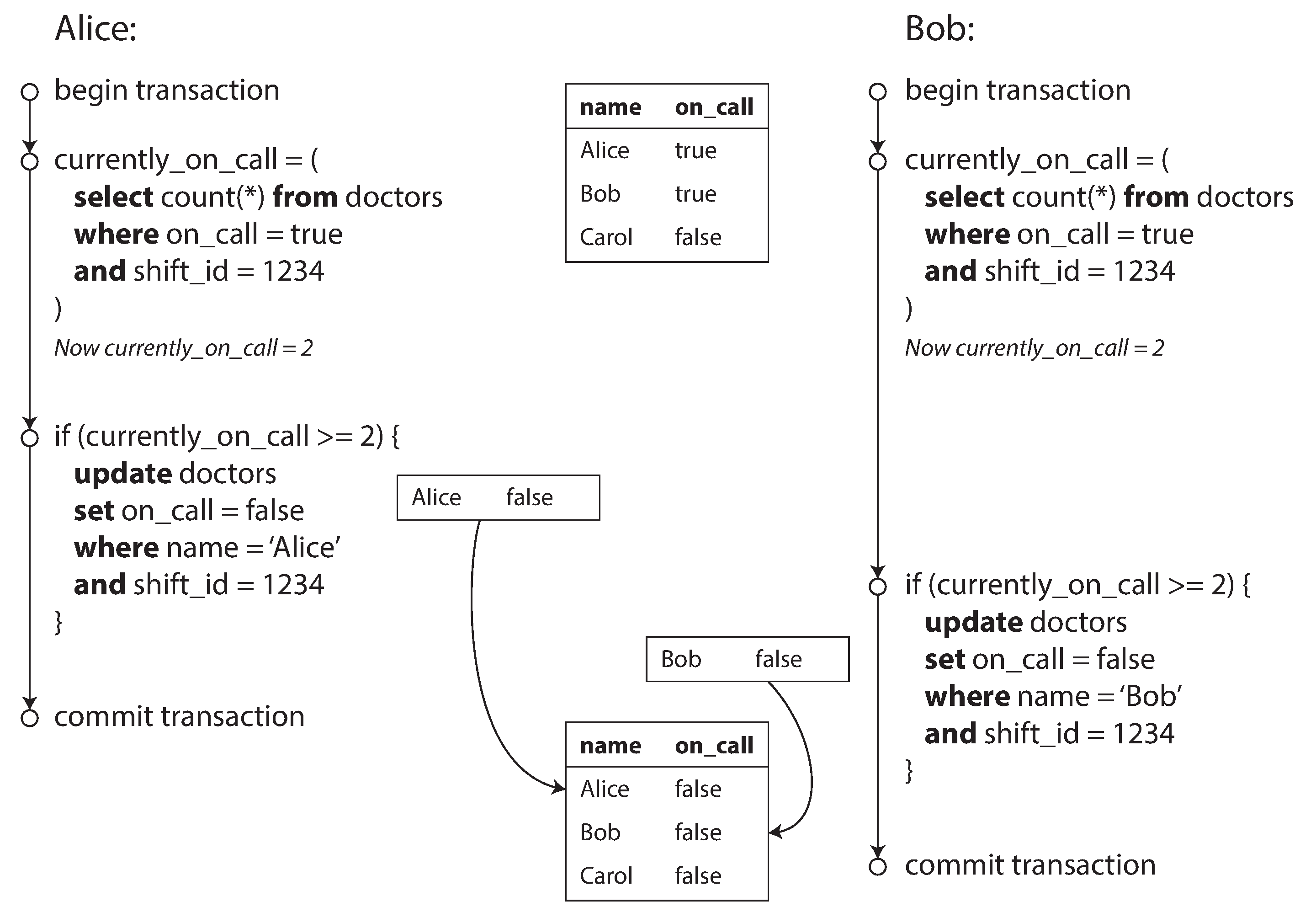

Write Skew

Generalizatioin of the lost update problem.

Phantom reads

A transaction reads objects that match some search condition. Another client makes a write that affects the results of that search. Snapshot isolation prevents straightforward phantom reads, but phantoms in the context of write skew require special treatment, such as index-range locks.

Serializable Isolation

the strongest isolation level

It guarantees that even though transactions may execute in parallel, the end result is the same as if they had executed one at a time, serially, without any concurrency. Thus, the database guarantees that if the transactions behave correctly when run individually, they continue to be correct when run concurrently—in other words, the database prevents all possible race conditions.

Serial execution of transactions has become a viable way of achieving serializable isolation within certain constraints: If you can make each transaction very fast to execute, and the transaction throughput is low enough to process on a single CPU core, this is a simple and effective.

Doesn’t scale that well though.

Two-Phase Locking

Writers block other writers, readers, and vice-versa. The blocking of readers and writers is implemented by having a lock on each object in the db, in shared mode or exclusive mode.

Doesn’t perform well though.

Pessimistic concurrency control mechanics: if anything might possibly go wrong, it’s better to wait until the situation is safe again before doing anything

Serializable Snapshot Isolation

A fairly new algorithm that avoids most of the downsides of the previous approaches. It uses an optimistic approach, allowing transactions to proceed without blocking. When a transaction wants to commit, it is checked, and it is aborted if the execution was not serializable.

Sources

Designing Data Intensive Applications